By Gary Berg-Cross

My education was a bit

deficient so I don’t remember running into the idea of neutral monism as part

of my training in Psychology and the questions of world materialism and mind idealism. A new book by Thomas

Nagel is provocatively entitle: “Mindand Cosmos: Why the Materialist Neo-Darwinian Conception of Nature Is Almost

Certainly False.” It features a skeptical take on materialism, but a naturalistic

and not theistic alternative. Nagel is well known for an interesting and influential 1974 paper called "What is it like to be a bat?" He used the bat view of the world to argue that phenomenological facts about consciousness are not so obviously reducible to physical facts. In his new book he argues that lack of progress in materialistically explaining suggests he is right in rejecting naïve materialist explanations. Early

on Nagel defines materialism succinctly as follows:

Materialism

is the view that only the physical world is irreducibly real, and that a place

must be found in it for mind, if there is such a thing. This would

continue the onward march of physical science, through molecular biology, to

full closure by swallowing up the mind in the objective physical reality from

which it was initially excluded. (p 37)

I’m not convinced by Nagel’s anti-materialist

arguments about the irreducibility of mind rather than matter, although I doubt

reductionist approaches that try to explain everything in reductionist

concepts. I like evolutionary explanations for the emergence of cognition and the related concept of consciousness. But I did find the discussion of neutral monism stimulating, if

only because I had missed its presence in thinkers I had studied. I also appreciated Nagel's conversational style and in Mind and Cosmos and his frank admission that his aim "is not so much to argue against reductionism as to investigate the consequences of rejecting it". This blog is not so much about that as a some intro to neutral monism.

As covered in the Wikipedia entry neutral monism is the

philosophical/metaphysical view that:

the mental and the

physical are two ways of organizing or describing the same elements, which are

themselves "neutral," that is, neither physical nor mental. This view

denies that the mental and the physical are two fundamentally different things.

Rather, neutral monism claims the universe consists of only one kind of stuff,

in the form of neutral elements that are in themselves neither mental nor

physical. These neutral elements might have the properties of color and shape,

just as we experience those properties. But these shaped and colored elements

do not exist in a mind (considered as a substantial entity, whether

dualistically or physicalistically); they exist on their own.

It’s an exciting idea of

continuity of reality rather than dichotomy and some faint versions of it were

quietly posed in works by some of my favorite philosopher – James, Russell and

Dewey as cited.

OK, it wasn’t just my education. The ideas were probably too subtle for me

to grasp when I dashed over their discussion of mind-body dualism. William

James, for example, followed Peirce in developing Pragmatism as a way of

getting beyond dualist debates on realistic materialism and idealism.

the philosophy of mind

adopted by Russell in his middle period was neutral monism, which denies that

there is any irreducible difference between the mental and the physical and

tries to construct both the mental world and the physical world out of

components which are in themselves neither mental nor physical but neutral. He

adopted this theory because he believed that there was no other way of solving

the problems that beset his earlier dualism (see Russell's

philosophy of mind: dualism). The book in which he developed the theory, The Analysis of Mind (1921), is an

unusual one. The version of neutral monism defended in it is qualified in

several ways and it is enriched with ideas drawn from his reading of

contemporary works on behaviourism and depth psychology. The result is not

entirely consistent, but it is interesting and vital especially where it is

least consistent.

John Dewey followed James in seeing more continuity

between mind and brain than a gulf. Like many my brief exposure to philosophy

courses left me somewhere in the pragmatic camp with a healthy respect for

reality-based materialism as the hull hypothesis. Dewey account of phenomena like intelligence does have a

naturalistic basis that integrates biology & psychology as does Nagels’ new

work. But one is surprised to see have non-reductionist

subjects of intentions and communication ala social psychology as front and

center in Dewey’s new view. It is

interesting to bump into some of these thinker’s metaphysical struggles to

reconceptualize our view of nature to resolve the issues, even if one does not

follow into a form of panpsychism with mind and consciousness everywhere

and everytime in the universe.

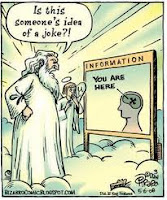

Images

Mind-Body Dualism: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Dualism-vs-Monism.png